Life

Adolfo Correia Rocha was born on August 12, 1907 in S. Martinho de Anta, municipality of Sabrosa, district of Vila Real, between the "warm earth" of schist from the Douro and the "cold earth" of granite from northeastern Trás-os-Montes. The village, humus that feeds his childhood, appears with the name Agarez in the autobiographical novel A Criação do Mundo, in a mythical projection of the native clod.

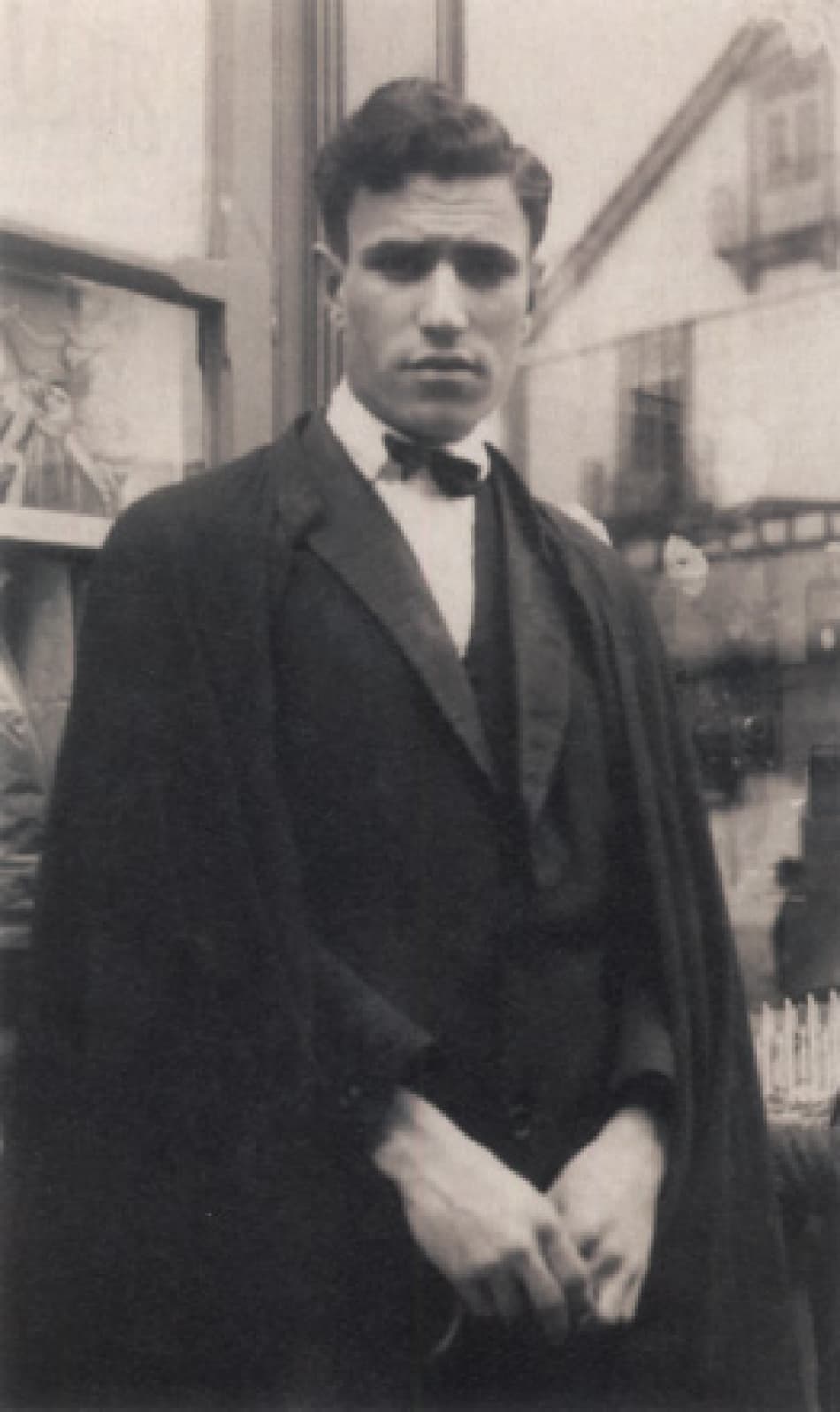

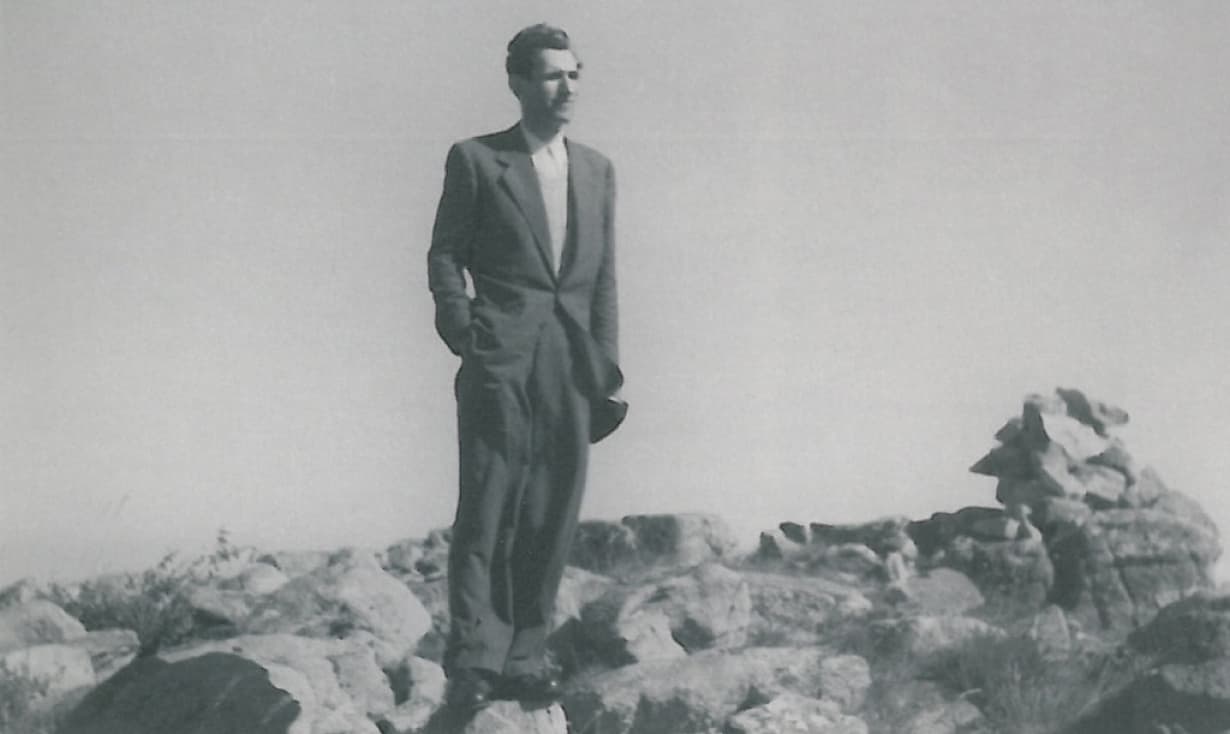

He grows up in a poor, honorable family, determined to open horizons for him. The father, Francisco Correia Rocha, blond, with blue eyes, is the vital stake. The mother, Maria da Conceição de Barros, almost green eyes, sweet voice, the warmth of the sentimental lap. He completes the fourth grade with distinction. Servant in Porto, one year at the Seminary of Lamego, the certainty that he doesn't want to follow the priesthood. At thirteen he leaves for Brazil to work on his uncle's farm, in Leopoldina (Minas Gerais). He returns five years later, does high school in three years and completes his degree in Medicine at the University of Coimbra, in 1933, with an average of 15 values. He returns to S. Martinho de Anta, and then practices in Vila Nova de Miranda do Corvo, in Leiria and, finally, in Coimbra.

In 1934, he adopts the literary name Miguel Torga. Miguel in homage to two great figures of Iberian culture, Cervantes and Unamuno. Torga in homage to the mountain heather, with hard roots and white or purplish flower. He travels through Europe to Italy, crossing a Spain wounded by the Civil War. The book "O Quarto Dia" of A Criação do Mundo (1939) is seized, the writer is arrested in Leiria and then taken to Aljube, where he remains for three months. In prison he writes the poem "Ariane" and some of the stories that make up the volume Bichos.

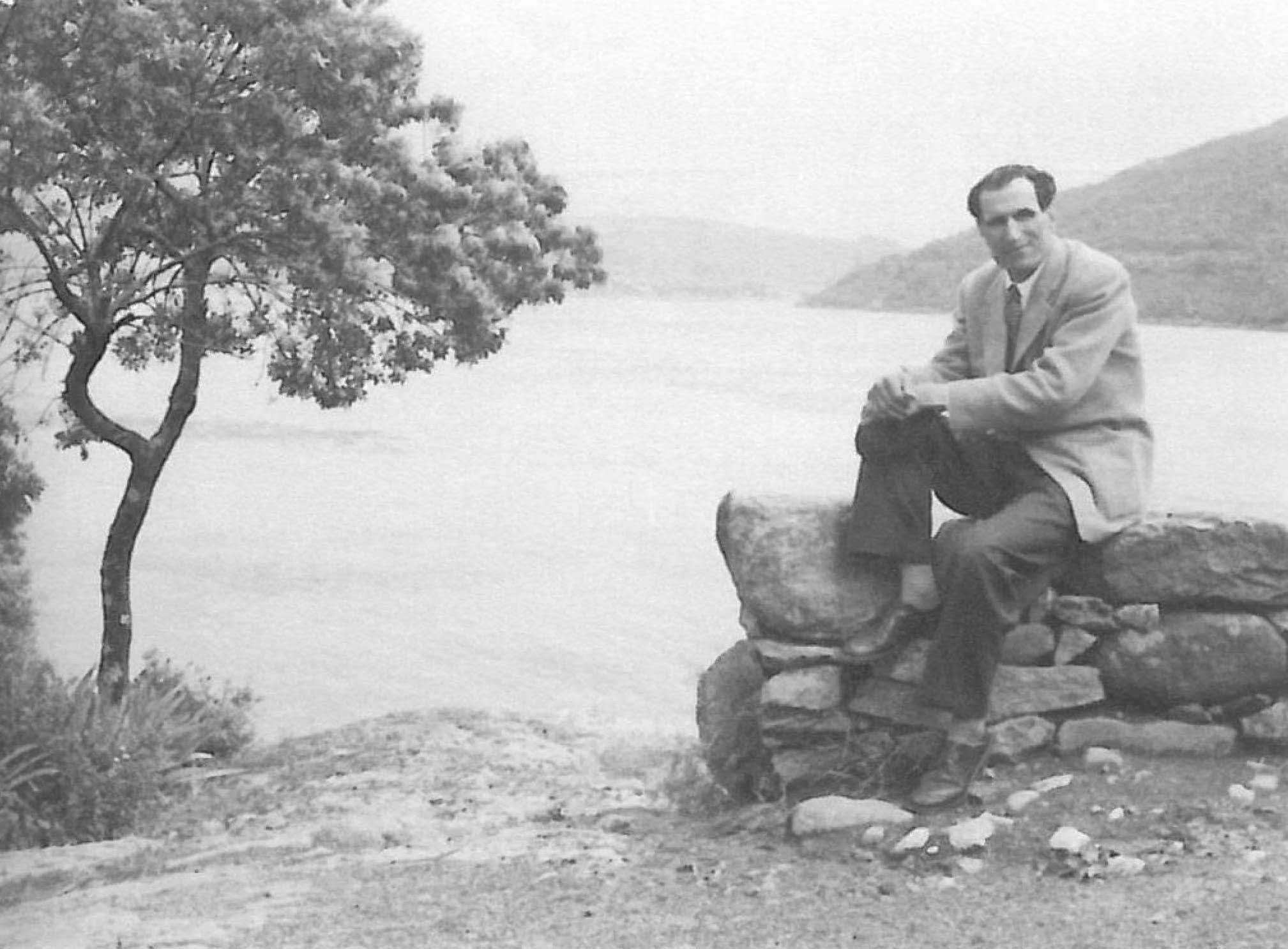

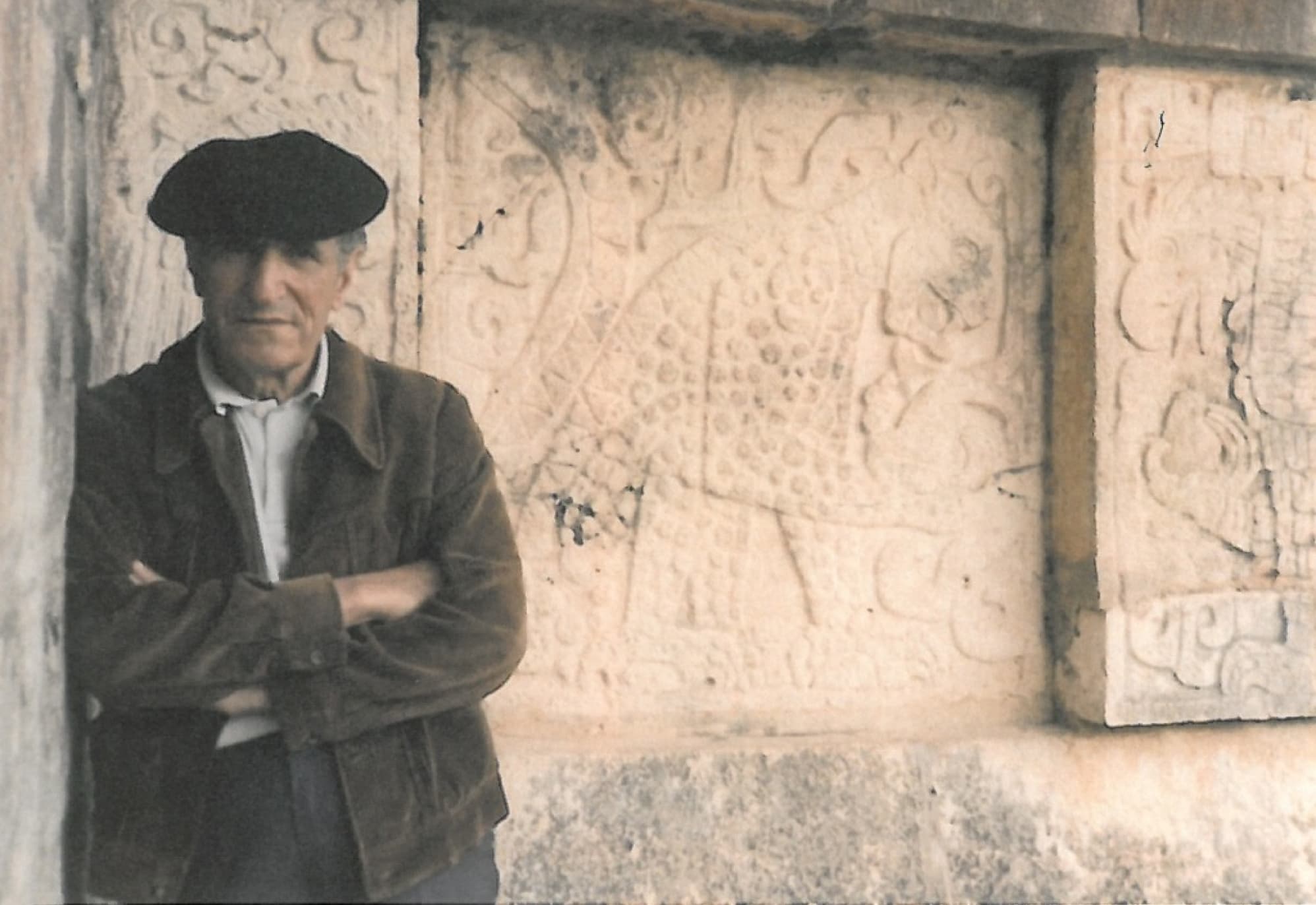

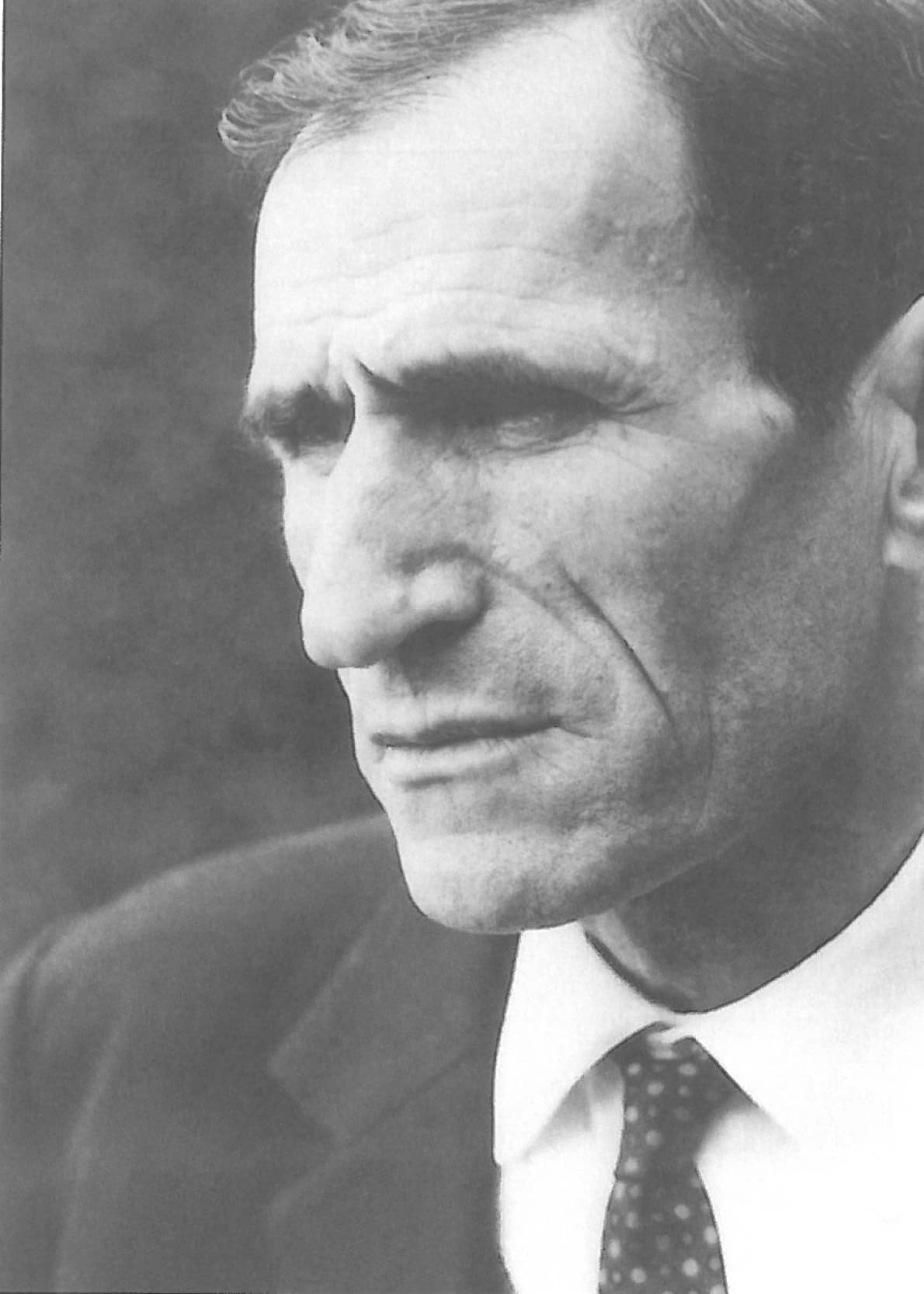

He is an unsatisfied author, writes in duplicate, on a typewriter with carbon paper. And rewrites. He corrects by hand, cuts strips of paper that he glues on top of the sheets. His days are diary, poetry, novel, short story, theater, intervention pages. Dedicated doctor, specialist in ears, nose and throat, in 1940 he opens a practice at Largo da Portagem, nº 45, in Coimbra, where he practices for more than fifty years. He travels incessantly through Portugal and the world, recording the physical, social and cultural landscape. He is also a hunter, left-handed with the weapon, strong-legged, shoots partridges, rabbits and hares through mountains and hills. He is one of the most influential Portuguese poets and writers, author of a vast literary production. Laureate with various national and international literary prizes, he receives the first Camões Prize in 1989 and is proposed five times for the Nobel Prize in Literature. For many years, he is the editor of his own books.

He dies on January 17, 1995. He is buried in the cemetery of S. Martinho de Anta, in a flat grave, with a torga nearby.